The Proliferation of Pictures

Introducing text

On how reposting was invented by Pop-Art, and what that says about the presentday media.

Essay

“Long before social media, this principle – extracting, reposting, giving something a new meaning – was demonstrated in the field of art.”

It was a piece of legislation that drove tens of thousands of people onto the streets – above all young people. The reform of copyright law, which was passed by the EU parliament despite fierce protests, is aimed at preventing material protected by copyright from being published without the consent of the copyright holder. What concerned the protesters was nothing less than a free internet – including the possibility to post images, films and music – for example in the form of memes, in other words text-image combinations, which spread virally online. As the strength of feeling directed against the threatened upload filter clearly showed: these days, reposting third-party material is regarded as an extension, perhaps even as an original expression of one’s digital personality.

Long before social media, this principle – extracting, reposting, giving something a new meaning – was demonstrated in the field of art. The principle of citation, in other words the eloquent reference to external material, whether motifs or styles, is probably as old as art itself. Marcel Duchamp and his ready-mades radicalized this process by means of a hard media disruption. With his infamous “Fountain” (1917), an inverted urinal, he was also concerned with deconstructing the difference between making art and proclaiming art. When Andy Warhol appropriated the images of others in the early 1960s, such as a press photo for the Marilyn Monroe movie “Niagara” (1953), and reproduced them using a screen-printing method, it was something completely different. Duchamp’s gesture also ingeniously demonstrated the impertinence of ripping something out from its material context. At first glance, Warhol operated in a more discreet manner, but ultimately he was more radical. He worked in the same medium: the image. The existing material already had its own aesthetic quality, showing the film diva at her most seductive. When Warhol printed the diva on a golden background, he endowed her with a religious aura. Yet by this time, Monroe’s sanctity had already been broken: she died in a mysterious manner. Whether by suicide or contract murder (speculation continues to run rife), her death was not least the product of a society that feasts just as much on the fame of its stars as on their demise. Warhol was not interested in criticizing this fact. Rather, displacing the picture produced a meshwork containing fame and tragedy, glamour and death, and the complex relationships between them. Long before sampling became widespread in pop and social media, Warhol demonstrates here one of the main characteristics of postmodern “reposting”. The old context is nullified as a citation, but replaced by a new one, resulting in an oscillation of meaning. One aspect, which was a constitutive part of Warhol’s strategy, was a confusion of authorship. The screen-printing method was conducive in this respect. In 1963 he declared: “I think it would be so great if more people took up silk screens so that no one would know whether my picture was mine or somebody else’s.”

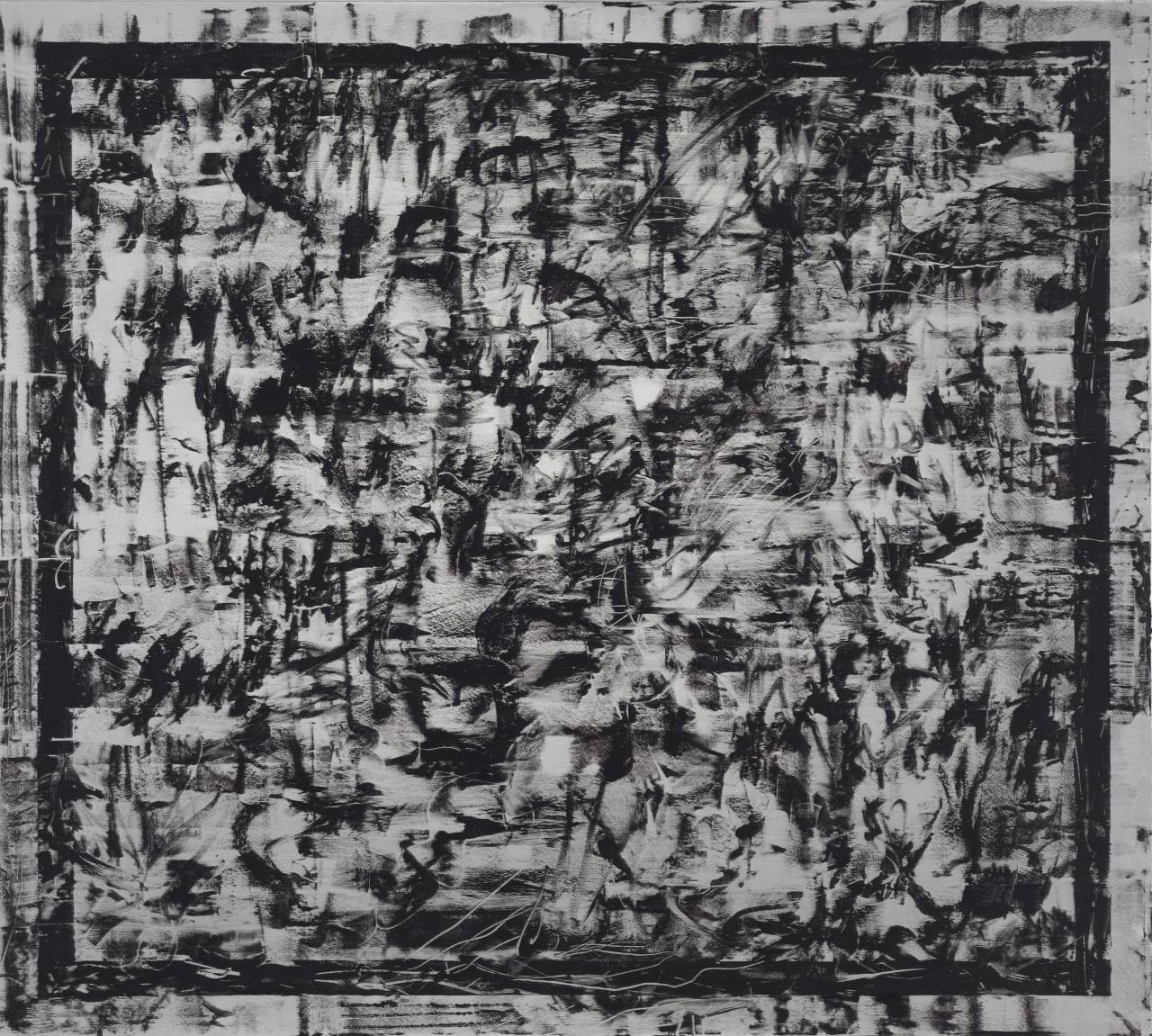

The artist Elaine Sturtevant took this encouragement seriously. In 1964 she took Warhol’s silk screen of the “Flowers” series and used it to create her own pictures, which she logically called “Warhol Flowers”. Shortly afterwards she wanted to work with the “Marilyn” silk screen, but because Warhol could no longer find it, she found an identical Marilyn photo and in this manner created her first work “Warhol Marilyn” (1965; a later reprise of this piece, “Warhol Black Marilyn” from 2004, can be seen in the exhibition). Sturtevant was not aiming to make an exact copy. Rather, she redirected the pictorial logic of Pop Art – reproducing existing motifs – back to the area of fine art. With her deliberately incomplete replicas she wanted to “trigger vertigo”, she admitted. This is particularly apparent in the case of her “Marilyn”. The contour of her lipstick is smudged, turning the smile into a grimace. That which was already suggested by Warhol becomes evident with Sturtevant: “Marilyn” is an image of transience.

With her working methods, Sturtevant represents a movement that is often called “Appropriation Art”. Following the postmodern deconstruction of authorship, the focus here is no longer on the original expression, but instead, as Jacob Proctor, curator at Museum Brandhorst, calls it, “doing something with images” – meaning: those of others. In this respect, Louise Lawler assumes a special position here. Her work “Plexi (adjusted to fit)” (2010/11) presents Warhol’s famous “Boxes”, which were created from the mid-1960s. Warhol made objects based on packaging samples. Lawler does not merely photograph these. At a closer glance it can be seen that the boxes here are behind a thin sheet of Plexiglass – because they are now being exhibited in museums, where Lawler photographs them. The objects made serially by Warhol at the time have now become expensive works of art that must be carefully preserved. It is a conflict of interest that is especially visible in the presentation of Warhol’s “Boxes”.

Wolfgang Tillmans shows that it is also possible to repost one’s own material, by placing photos of the rave scene, which he took for lifestyle magazines, in the context of art. And again we observe a shift in meaning. What was once still celebrated in the magazines of the early 1990s as a vibrant present now seems like a melancholic memory of a subcultural utopia that was soon threatened with sellout.

In the early 1960s, at the beginning of this artistic development, the means of reproduction were still mechanical, and complex. In the digitally dominated present, copying and reposting is often merely a matter of a few clicks. This results in, as Jacob Proctor calls it, a “hypertrophy of contemporary image culture”, which admittedly was already incipient in the analogue age of printing, but which now represents our everyday media life. We measure the world in images, think in images, we communicate in images. In the process, we all too easily forget what art shows us: that images do not necessary refer to that which we call “reality”, but above all to other images.